Viviendo al borde del abismo

Fuente : http://fraukedecoodt.wordpress.com/2012/01/07/living-on-the-edge/

Artículo relacionado : http://desobedientes.noblogs.org/post/2011/10/25/policia-reprime-protesta-frente-a-la-usac/

Independiente del movimiento ocupa en América del Norte y Europa, un movimiento de habitantes de barrios pobres en Guatemala está ocupando la calle en frente del Congreso. Están protestando contra las condiciones de vida en los barrios pobres y una política de vivienda disfuncional. Para cambiar su situación en la que no sólo ocuparon el Congreso; también hicieron un proyecto de ley y finalmente, comenzaron una huelga de hambre.

Mientras la crisis y la pobreza aumentan en el mundo occidental, los activistas en Europa y América del Norte están ocupando plazas de la ciudad por todas partes.

En la ciudad de Guatemala, sin embargo, existe un movimiento independiente, donde los activistas han ocupado la calle frente al Congreso desde el 22 de agosto 2011 . Aquí, las casas cálidas no fueron sacrificadas por tiendas de campaña, chozas miserables han sido cambiadas por tiendas de campaña. Los activistas de los barrios pobres se han comprometido a no salir hasta que la «Ley de Vivienda» sea aprobada – exigiendo una solución para la crisis de vivienda en Guatemala. La falta de un alojamiento accesible fuerza a innumerables guatemaltecos a vivir en barrios de asentamientos humanos donde las condiciones de vida precarias suelen tener consecuencias letales. El 22 de noviembre, la ley que se ha luchado durante años, una vez más no ha recibido su aprobación. En respuesta, tres personas del campo fuera del Congreso iniciaron una huelga de hambre.

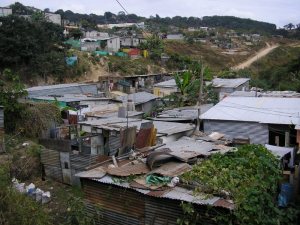

Los barrios pobres de Guatemala

Mires donde mires hay carteles en el campamento. Las tiendas de color caqui, fueron entregados a las favelas después de un desastre natural. La electricidad es proporcionada por una escuela que está frente al congreso y los baños de plástico fueron donados por los movimientos sociales que los apoyan. En el campamento un fuego de carbón está ardiendo. Los acogedores activistas, sobre todo mujeres y sus hijos platican, en gran medida hacen caso omiso de la televisión. «Las condiciones son mejores que las que vivimos», me aseguran.

Los manifestantes son algunos de los 1,5 millones de habitantes de los barrios pobres de Guatemala. Los asentamientos humanos están en todas partes, en las ciudades y el campo. Las recientes cifras exactas no están disponibles. Dentro del campamento Roly Escobar, el representante de la organización CONAPAMG, está teniendo una reunión con algunos de sus compañeros activistas. Buscamos un lugar tranquilo para hablar. Escobar tiene un conocimiento profundo de la situación de haber luchado durante años por los derechos de los barrios pobres. Escobar afirma que en Guatemala más de 800.000 familias viven en chozas en los 982 barrios pobres de Guatemala. Alrededor de 420 de ellas están situadas en los alrededores de la ciudad de Guatemala. Según los expertos de un quinto a un tercio de los 2,5 millones de habitantes del área metropolitana residen en lugares precarios.

Los residentes llaman a sus barrios «asentamientos». Ellos sienten que esta es una descripción más digna y más exacta de los asentamientos como pueden variar en tamaño de una casa a todo un barrio. «Sólo las personas pobres viven en los asentamientos, se ven obligados a asentarse en tierras que no son propietarios», dice Escobar. «A menudo, esto es terreno baldío en el que nadie quiere vivir, en el borde de barrancos, laderas empinadas y adyacentes o en los vertederos de basura.»

Después de salir de las calles a vivir en los barrios pobres, Luis Lacán rápidamente se dio cuenta de la necesidad de la solución los habitantes y los problemas que enfrentan. Se unió a UNASGUA – una organización que ofrece apoyo legal a aquellos que luchan para mejorar las condiciones en los barrios pobres. Cuando nos sentamos en su humilde oficina Lacán explica que «las condiciones de vida son precarias, porque siempre la tierra ocupada no tiene nada, ni agua, ni electricidad, ni alcantarillado, ni calles pavimentadas, nada».

Lacán se preocupa por sus compañeros de habitantes de barrios pobres. Él explica que no se puede conectar el agua y la electricidad sin ser capaz de demostrar el derecho legal a la ocupación. Los asentamientos no están incluidos en los planes oficiales para el desarrollo regional y urbano y por lo tanto no se consideran para la inversión en infraestructura. Esto a veces tiene consecuencias desastrosas para la seguridad y la salud de los residentes.

Sobre el tiempo los residentes a menudo comienzan a organizarse, adquirir algunas áreas de electricidad y agua, algunas chozas de parecerse más a las casas, mientras que otros se asemejan a cajas de cartón. Sin embargo, a pesar de la edad de un asentamiento, sin la legalización, el temor al desalojo está siempre presente.

Sobrevivir en los suburbios

«La mayoría de las familias de nuestros barrios viven en casas hechas de láminas oxidadas, cartón y plástico. Algunas familias ni siquiera tienen eso «, dice Brenda, una de las activistas que acampan fuera del Congreso. Una joven madre, Julia, añade, «sin sistemas de alcantarillado todas las aguas residuales de los barrios que rodean pasa por nuestras champas (chozas), champas, que tienen pisos de tierra. Es un caldo de cultivo para las enfermedades e infecciones. Nuestros hijos se enferman, a veces se mueren, simplemente porque carecen de una vivienda digna. Mi hija tenía dieciocho meses de edad cuando ella se enfermó y murió. »

Brenda mueve la cabeza afirmativamente «durante la temporada de lluvias, muchas personas viven en el barro. El agua fluye a través de sus champas. Los niños y los ancianos son especialmente susceptibles a la neumonía y la bronquitis y las muertes no son infrecuentes. Recientemente, una anciana murió en mi barrio de la bronquitis. Debido al huracán Agatha en 2010, vivía en una casa construida de cartón y plástico. Mi barrio sufrió mucho entonces. «

La desnutrición tiene un impacto enorme en la salud y el desarrollo de los residentes, especialmente los niños. Según cifras de las Naciones Unidas la mitad de los guatemaltecos vive por debajo del umbral de la pobreza, y la mitad de los niños están desnutridos. Estas cifras son la realidad cotidiana de los habitantes de barrios pobres. «No tenemos suficiente dinero para comprar comida para nuestros hijos. Con las privatizaciones se hizo todo más caro, la comida, agua, gas, electricidad «, explica Brenda con indignación. Escobar subraya que no sólo los niños pequeños, sino que los habitantes de la mayoría de los asentamientos están desnutridos. «¿Cómo es esto posible en un país tan rico? Sin trabajo y sin ingresos las personas morirán de hambre aquí. Esto ya está sucediendo. Recientemente, tres adolescentes de quince años de edad, murieron de desnutrición. «

Otra causa común de muerte en estos barrios es la violencia. Los barrios pobres se asocian a menudo con pandillas notoriamente brutales. Escobar, cuyo hijo fue asesinado, quiere poner este tipo de violencia en su contexto. «Si no hay trabajo, ni escuelas, ni nada que hacer, y tiene el nivel de pobreza donde los padres no pueden permitirse el lujo de alimentar a sus hijos o enviarlos a la escuela, entonces van a la criminalidad. Los jóvenes se convierten en presa fácil de poderosas organizaciones criminales. Estos problemas no han nacido aquí y no sólo se producen aquí. En conjunto Guatemala está plagada de narcos y violencia. «

Muchos de sus habitantes se sienten sin esperanza. Doña Rosa, una anciana que se une como Brenda y Julia a platicar no puede contener las lágrimas. «¿Qué pasará si me muero? Tal vez nunca veré la legalización».

Una pobre política de vivienda y un creciente problema de la vivienda

«¿Por qué ir a vivir a un barrio en el borde de un abismo o en una pendiente empinada montaña? No porque queremos vivir así, sino porque tenemos la esperanza de sobrevivir. La gente vive aquí porque no tienen otra opción, no hay vivienda viable y accesible. Demasiadas personas no tienen dónde vivir «, explica Brenda, mientras que su hija de cinco años salta para captar su atención.

Las razones por las que hay tantos barrios pobres hacinados son diversas. El reciente conflicto armado, desastres naturales, el crecimiento demográfico y la falta de tierra o de trabajo en el campo han obligado a muchos guatemaltecos a emigrar a la ciudad y vivir en los barrios pobres.

Las cifras oficiales estiman que para finales de 2011 habrá una escasez de viviendas de 1,6 millones de hogares, de los cuales 15% será en la ciudad de Guatemala. «El aumento de la demanda excede la capacidad del Estado para resolver la escasez de viviendas que incurra», concluye el SEGEPAZ institución estatal. Los expertos sobre la crisis de vivienda y residentes de los asentamientos acuerdan en que el gobierno nunca ha tratado de encontrar una solución al problema de la vivienda. ASIES, una institución de investigación, encontró que desde 1956 la acción del gobierno en materia de vivienda ha consistido en iniciativas esporádicas realizadas por las instituciones ineficientes y las intervenciones de política insuficiente, lo que resulta en la acumulación de una enorme escasez de viviendas.

Para remediar esta situación, la primera «Ley de la Vivienda» fue finalmente aprobado en 1996. Supervisado por el Ministerio de Comunicaciones, Infraestructura y Vivienda, la iniciativa de vivienda nueva con un presupuesto ridículamente bajo. El corrupto desvío de fondos por funcionarios del gobierno, empresas constructoras, y representantes de organizaciones de barrios han dejado poco para proveer a las personas con necesidades de vivienda. Solicitar una subvención al amparo del régimen no sólo es un proceso muy largo y burocrático, sino que también requiere que el solicitante añada una considerable suma de dinero, algo que muchos no tienen. «Dado el tamaño del problema de la vivienda, estaba claro que esta ley no era una solución», concluye Lacan.

La política de vivienda de las últimas décadas se caracterizó principalmente por soluciones cosméticas afirma Helmer Velásquez del diario El Periódico. «Los residentes primero deben ocupar lo que es básicamente un pedazo de tierra inhabitable con el fin de llamar la atención de las autoridades. Después de un tiempo se les proporciona «importante» infraestructura, tales como gradas y callejones pavimentadas. Especialmente durante las elecciones se piensa acerca de las condiciones en los barrios pobres y sobre la legalización. Lacan afirma que «sólo durante las elecciones los políticos encuentran el camino a los barrios pobres. Entonces vienen con regalos tales como láminas y concreto, con promesas como el empleo, la educación y la salud «.

De proyectos de ley a huelgas de hambre

Como resultado de estos múltiples problemas, los residentes de barrios pobres y movimientos sociales relacionados comenzaron a trabajar en un proyecto de ley, a partir de sus propias experiencias, la Constitución, las leyes nacionales y los tratados internacionales de las Naciones Unidas que garantizan el derecho a la vivienda. La Universidad de San Carlos y las instituciones pertinentes del Estado pulieron la propuesta. Lacán continúa: «En 2008, el proyecto de ley fue presentado al Congreso. Allí también, la propuesta fue revisada y, finalmente concedida por los comités del Congreso. Desde entonces se ha quedado atascada. El proyecto de ley sólo debe ser releído y aprobado, en principio, una mera formalidad. «

El 23 de agosto de 2011, cuando el proyecto de ley no fue aprobado de nuevo por enésima vez, algunos activistas decidieron crear un «Asentamiento Congreso», acampando frente a las puertas hasta que sean escuchadas. «Así que muchos gobiernos han ido y venido y nadie nos ha tenido en cuenta. Ahora estamos aquí y nos quedamos hasta que se apruebe el proyecto de ley «, afirma doña Rosa combativamente.

«Luchamos por una ley que beneficiará a toda la población guatemalteca», enfatiza Brenda. «Exigimos que las champas se conviertan en hogares habitables, que nuestra tierra y nuestras casas estén legalizadas por lo que finalmente se puedan conectar los servicios básicos, exigimos la provisión de viviendas a las familias que realmente lo necesitan».

Escobar quiere instituciones con responsabilidad social y política de vivienda dirigidas por un ministerio de vivienda especial. Una buena política de vivienda tiene que tener una buena ley como sus fundamentos.

Sin embargo, los académicos señalan que la ley y la legalización no es suficiente. También se debe prestar atención a la educación, el empleo, las condiciones de vida, en definitiva, a un diferente modelo socio-económico que rompe el círculo vicioso de la pobreza. De lo contrario, los barrios pobres seguirá creciendo.

Pero después de casi cuatro meses frente al Congreso los habitantes de barrios pobres comienzan a perder la paciencia. Después de que el proyecto de ley fue rechazada de nuevo el 22 de noviembre tres residentes, incluida la joven madre Julia, decidieron iniciar una huelga de hambre.

Si esta nueva forma de protesta no funciona y el Congreso no aprueba el proyecto de ley, lo más probable es que no sólo serán víctimas más lejos, en los barrios pobres, sino también pueden ser víctimas frente a la puerta de los Representantes del Pueblo .

(Este artículo fue publicado por primera vez en Holandés el 02/diciembre/2011. En este día 07/enero/2012 los activistas aún se encuentran en frente del Congreso, pero se detuvo la huelga de hambre después de 19 días)

Roly.conapamg[at]yahoo.com

conapamg[at]yahoo.com

Movimiento Guatemalteco de Pobladores

(www.movimientoguatemaltecodepobladores.blogspot.com)

******************************************************

Living on the edge of the abyss

Independent from the Occupy Movement in North-America and Europe, a movement of slum dwellers in Guatemala is occupying the street in front of Congress. They are protesting against the living conditions in the slums and a disfunctional housing policy. To change their situation they not only occupied Congress but made a bill and eventually started a hunger strike.

As crisis and poverty escalate in the Western world, activists in Europe and North America are now occupying city squares everywhere.

In Guatemala City, however, an independent movement exists, where activists have occupied the street in front of Congress since the 22nd of August 2011. Here, warm houses were not sacrificed for tents, rather miserable hovels have been exchanged for tents. Activists from the slums have pledged not to leave until the “Housing Law” is approved – demanding a solution for the housing crisis in Guatemala. A lack of affordable accommodation forces uncountable Guatemalans into shantytowns where precarious living conditions often have lethal consequences. On the 22nd of November the law that has been fought for years once again did not receive approval. In response, three people from the camp outside Congress started a hunger strike.

The slums of Guatemala

Everywhere you look there are banners in the tent-camp. The khaki-colored tents were given to the shantytowns following a natural disaster. Electricity is provided by a school in the street and plastic toilets were donated by supportive social movements. In the camp a coal fire is smoldering. The welcoming activists, mostly chatting women and their children, largely ignore the television. “The conditions here are better than where we live” they assure me.

The protesters are some of the estimated 1.5 million inhabitants of the slums of Guatemala. Shantytowns are everywhere, in cities and in the countryside. Recent accurate figures are not available. Within the camp Roly Escobar, the sympathetic representative of the organization CONAPAMG, is having a meeting with his some fellow activists. We look for a quiet place to talk. Escobar has a thorough understanding of the situation having fought for years for the rights of poor neighborhoods. Escobar claims that in Guatemala more than 800,000 families live in shacks in the 982 Guatemalan slums. Around 420 of these are situated in and around Guatemala City. According to experts a fifth to one third of the 2.5 million inhabitants of the metropolitan area reside in precarious locations.

The residents call their shantytowns “settlements”. They feel this is a more dignified and accurate description as the settlements can vary in size from a house to a whole neighborhood. “Only poor people live in the settlements, they are forced to settle on land which they do not own” says Escobar. “Often this is wasteland where nobody wants to live, on the edge of ravines, on steep slopes and adjacent to or in garbage dumps.”

After leaving the streets to live in the slums, Luis Lacán quickly became aware of the needs of the settlement dwellers and the problems they face. He joined UNASGUA – an organization that offers legal support to those who fight to improve conditions in the slums. As we sit in his humble officeLacán explains “living conditions are precarious because invariably the occupied land has nothing, no water, no electricity, no drainage, no paved streets, nothing.”

Lacán worries about his fellow slum dwellers. He explains that you cannot connect water and electricity without being able to prove a legal right to occupancy. The settlements are not included in official plans for regional and urban development and so are not considered for infrastructure investment. This sometimes has disastrous consequences for the safety and health of residents.

Over time residents often start to organize themselves, some areas acquire electricity and water, some shacks become more like houses, while others still resemble cardboard boxes. However, in spite of the age of a settlement, without legalization, the fear of eviction is ever-present.

Surviving in the slums

“Most families in our neighborhoods live in houses made of rusty corrugated iron, cardboard and plastic. Some families do not even have that” says Brenda, one of the campaigners camped outside Congress. A young mother named Julia adds, “without sewage systems all the waste water from the surrounding neighborhoods passes by our shacks, shacks which have earth floors. It’s a breeding ground for diseases and infections. Our children get sick, sometimes they die, just because they lack a decent home. My daughter was eighteen months old when she became ill and died.”

Brenda nods affirmatively “during the rainy season, many people live in mud. Water flows through their shacks. Children and the elderly are particularly susceptible to pneumonia and bronchitis and deaths are not uncommon. Recently, an elderly woman died in my neighborhood from bronchitis. Because of hurricane Agatha in 2010 she lived in a house built from cardboard and plastic. My neighborhood suffered much then.”

Malnutrition has a huge impact on the health and development of the residents, especially children. According to figures from the United Nations half of Guatemalans live below the poverty line, and half the children are malnourished. These figures are the daily reality of slum dwellers. “We do not have enough money to buy food for our children. With the privatizations everything became more expensive; food, water, gas, electricity” explains Brenda indignantly. Escobar emphasizes that it is not only young children but that most settlement dwellers are malnourished. “How is this possible in such a rich country? Without work and income people will die of hunger here. This is already happening. Recently three fifteen year old teenagers died of malnutrition.”

Another common cause of death in these neighborhoods is violence. The slums are often associated with notoriously brutal gangs. Escobar, whose son was murdered, wants to put this violence in its context. “If there is no work, no schools, nothing to do, and you have the level of poverty where parents cannot afford to feed their children or send them to school then you are going to get criminality. Young people become easy prey to powerful organized criminals. These problems are not born here and do not only occur here. The whole of Guatemala is plagued by narcos and violence.”

Many inhabitants feel hopeless. Doña Rosa, an elderly woman who joins in as Brenda and Julia talk cannot restrain her tears. “What will happen if I die? Maybe I will never see this legalization.”

A lame housing policy and a growing housing problem

“Why do we go and live in a slum on the edge of an abyss or on a steep mountain slope? Not because we want to live like this, but because we hope to survive. People live here because they have no choice, there is no viable, affordable housing. Far too many people have nowhere to live” explains Brenda, whilst her five year old daughter jumps around catching her attention.

The reasons why there are so many overcrowded slums are diverse. The recent armed conflict, natural disasters, population growth and a lack of land or work in the countryside have forced many Guatemalans to migrate to the city and live in the slums.

Official figures estimate that by the end of 2011 there will be a housing shortage for 1.6 million households, of which 15% will be in Guatemala City. “The increasing demand exceeds the capacity of the State to resolve the incurred housing shortage” concludes the state institution SEGEPAZ. Those knowledgeable about the housing crisis and settlement residents agree that the government has never really tried to find a solution to the housing problem. ASIES, a research institution, found that since 1956 government action on housing has consisted of sporadic initiatives undertaken by inefficient institutions and of insufficient policy interventions, resulting in the accumulation of an enormous housing shortage.

To remedy this situation the first “Law for Housing” was finally approved in 1996. Overseen by the Ministry of Communications, Infrastructure and Housing, the new housing initiative received a ridiculously low budget. The corrupt siphoning of funds by government officials, building companies, and representatives of neighborhood organizationshas left little to provide for those with housing needs. Applying for a grant under the scheme is not only a very long and bureaucratic process, it also requires the applicant to add a considerable sum of money, something many do not have. “Given the size of the housing problem, it was clear that this law was not a solution” concludes Lacán.

The housing policy of the last few decades was mainly characterized by cosmetic solutions claims Helmer Velásquez from the newspaper El Periodico. “Residents must first occupy what is basically an uninhabitable piece of land in order to gain the attention of the authorities. After a while they are provided with “important” infrastructure such as stairs and paved allies. Especially during the elections there is thought about the conditions in the slums and about legalization.” Lacán affirms that “only during elections politicians find the way to the slums. Then they come with presents such as corrugated iron and concrete, with promises such as employment, education and health.”

From bills to hungerstikes

As a result of these myriad problems, shantytown residents and related social movements began working on a bill themselves, drawing on their own experiences, the Constitution, national laws and the international treaties of the United Nations which guarantee the right to housing. The University of San Carlos and relevant state institutions further refined the proposal. Lacán continues , “In 2008 the bill was presented to Congress. There too, the proposal was revised and eventually consented by Congressional committees. Since then it is stuck. The bill should only be reread and approved, in principle, a formality.”

On 23rd August 2011, when the bill was again not approved for the umpteenth time, some activists decided to set up a “Shantytown Congress”, camping in front of the doors until they are heard. “So many governments have come and gone and no one has ever taken us into account. Now we are here and we stay until they approve the bill” declares the elderly Doña Rosa combatively.

“We struggle for a law that will benefit the entire Guatemalan population” emphasizes Brenda. “We demand that shacks are changed into livable homes, that our land and our homes are legalized so we can finally connect basic services, we demand that housing is provided to families who really need it.”

Escobar wants socially responsible institutions and housing policy directed from a dedicated housing ministry. A good housing policy needs to have good law as its foundations.

Academics however point out that a law and legalization are not enough. Attention should also be paid to education, employment, living conditions, in short to a different socio-economic model which breaks the vicious circle of poverty. Otherwise, the slums will continue to grow.

But after nearly four months in front of Congress the slum dwellers begin to lose their patience. After the bill was rejected again on November 22 three residents, including the young mother Julia, decided to start a hunger strike.

If this new form of protest does not work and Congress does not approve the bill, it is likely that there will not only be further victims far away in the slums but there may also be victims in front of the door of the Representatives of the People.

(This article was first published in Dutch on 2.12.2011. On this day 7.01.2012 the activists are still in front of Congress, but stopped their hunger strike after 19 days)

Roly.conapamg[at]yahoo.com

conapamg[at]yahoo.com

Movimiento Guatemalteco de Pobladores

(www.movimientoguatemaltecodepobladores.blogspot.com)

Tags: 15 m, asentamiento congreso, Frauke.Decoodt, indignados, ley de vivienda 38-69, occupy wall street, ocupa, ocupa wall street, Ocupación

noviembre 29th, 2013 at 18:57

[…] redención de los Caballos y Los Metales” y “Guatemala: viviendo al borde del abismo”, narran la realidad de muchos guatemaltecos que viven en áreas marginadas de las afueras de la […]

marzo 20th, 2015 at 19:26

[…] redención de los Caballos y Los Metales” y “Guatemala: viviendo al borde del abismo”, narran la realidad de muchos guatemaltecos que viven en áreas marginadas de las afueras de la […]